In 2017, seven years after a woman was sexually assaulted in broad daylight police in South Florida turned to the forensic DNA phenotyping company Parabon NanoLabs in a last resort attempt to identify a suspect.

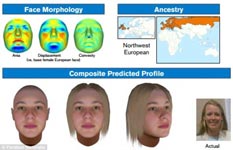

Within a few weeks, the Virginia-based company provided Davie police with a composite sketch based on an analysis of DNA recovered from the victim that described a male with light brown skin, brown-hazel eyes and black hair.

Armed with the sketch, police recanvassed the crime scene and came to conclude that the perpetrator likely worked at Flamingo Gardens, a nearby wildlife attraction. There, investigators encountered a man with matching features and convinced him to let them take a sample of his DNA. When tests showed his DNA exhibited the same pattern of genetic variations as that found on the victim, police knew they had finally solved the cold case. The chances of two people sharing the same such pattern, are 1 in 400 billion. [1]

Armed with the sketch, police recanvassed the crime scene and came to conclude that the perpetrator likely worked at Flamingo Gardens, a nearby wildlife attraction. There, investigators encountered a man with matching features and convinced him to let them take a sample of his DNA. When tests showed his DNA exhibited the same pattern of genetic variations as that found on the victim, police knew they had finally solved the cold case. The chances of two people sharing the same such pattern, are 1 in 400 billion. [1]

The tale is one of dozen told by advocates of Forensic DNA Phenotyping, which uses DNA analysis to compose a physical description of an individual. The technology can predict gender with 100 percent accuracy and externally visible characteristics, or EVCs in genetic parlance, such as hair and eye color, skin tone and height with at least 70 percent accuracy within some populations, according to multiple scientific studies.

Many in law enforcement believe it can dramatically improve clearance rates of cases where the perpetrator’s DNA profile has not yet been added to criminal DNA databases. The technology has already helped police worldwide close cold cases and identify bodies following crimes and natural disasters.

How it works

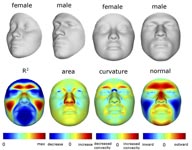

Phenotyping is based on the same genetic sequencing technology used by medical researchers to identify variations in human DNA that are biomarkers for disease. This is done by finding rare variations in the sequence of our genetic code called “single nucleotide polymorphisms” (SNPs) that correspond to thousands already known to correlate with physical traits.

For instance, the color of our iris is determined by SNPs in and near pigmentation genes that code for melanin and other proteins that determine hair and skin color, including freckles. Darker eyes have more melanin than lighter colored eyes.

For instance, the color of our iris is determined by SNPs in and near pigmentation genes that code for melanin and other proteins that determine hair and skin color, including freckles. Darker eyes have more melanin than lighter colored eyes.

Parabon’s Snapshot DNA phenotyping service does this by comparing SNPs from the DNA sample to millions of SNPs and billions of SNP combinations collected from thousands of individuals in its database. It then uses a proprietary data mining, machine learning and statistical model called Parabon Crush™ to translate those biomarkers into “forensically relevant trait predictions.” [2] The company says it can take hundreds of computers running weeks at a time to complete the Snapshot process.

In the last five years, DNA-based techniques for predicting hair texture, dimpling, earlobe attachment, baldness, dominant hand, clef chins and even the shape and composition of the face have become more accurate.

Epigenetics researchers, meanwhile, can now estimate age based on the amount of DNA methylation found in samples with a standard deviation of just 3.15 years, according to research published in 2017. DNA methylation levels can also help determine whether someone suffers from schizophrenia and there is a growing library of biomarkers for diseases that can shine light on an individual’s likely lifestyle. Diabetics, for instance, may be prone to suck on hard candy, while those with lactose intolerance may avoid dairy and those with biomarkers for certain diseases may be heavy smokers or drinkers.

Excluding suspects early in an investigation

DNA phenotyping, of course, has the same limitations as any genetic technique. Most physical traits are polygenic, meaning they are the result of multiple genes interacting. Eye color, for instance, is determined by at least six SNPs working in concert, not to mention epigenetic factors such as food they eat and prescription drugs they take, and even whether they have a headache or are in a bad mood. By 2014, scientists suspected nearly 700 biomarkers influence height.[3]

DNA phenotyping, of course, has the same limitations as any genetic technique. Most physical traits are polygenic, meaning they are the result of multiple genes interacting. Eye color, for instance, is determined by at least six SNPs working in concert, not to mention epigenetic factors such as food they eat and prescription drugs they take, and even whether they have a headache or are in a bad mood. By 2014, scientists suspected nearly 700 biomarkers influence height.[3]

While the IrisPlex System launched in 2010 can now differentiate between blue and brown eye color with 90 percent or better accuracy, it is less effective at predicting intermediate eye colors such as hazel or green, or the eye color of Asians.[4]

But while DNA phenotyping can’t establish identity beyond a shadow of a doubt, it can establish a high level of probability that can help investigators rule out certain suspects early in an investigation.

Being able to confirm a suspect’s skin color and other features via DNA phenotyping rather than rely on witness accounts could save investigators thousands of hours in wasted manpower and help boost clearance rates. That was demonstrated in 2017 when the Costa Mesa Police Department learned the Pacific Islander suspect they had focused on in a 22-year-old homicide case did not match the features shown in a composite sketch provided by Parabon. Police subsequently identified a Hispanic man as the perpetrator and arranged to have him extradited from Mexico.

“The future of this technology is extremely promising and having the ability to generate a sketch from a DNA profile will positively impact and increase the clearance rates of violent crimes committed in California,” wrote Ronald Seman in an article that appeared in the Journal of California Law Enforcement in 2018.. [5]

Seman, a commander with the Orange County District Attorney’s Office in California, noted that California law enforcement cleared just 45.8 percent of 166,588 violent crimes reported in 2015 and just 12.6 percent of more than 1 million property crimes.

Science or science fiction

Given the enormous number of SNP combinations that could be associated with a physical trait, some scientists question whether an algorithm will ever be able to render an accurate sketch from a suspect’s DNA. More importantly, our physical appearance is shaped by many epigenetic factors. A suspect could dye or cut their hair, grow a beard, lose or gain weight, become emaciated from drug addiction, be disfigured in an accident or age prematurely due excessive exposure to the sun, smoking or excessive drinking. They could undergo plastic surgery or even change gender.

Also, it’s still not known if DNA codes facial and other features the same way from one ancestral group to another. In other words, the same genetic variation may manifest itself differently depending on someone’s ancestry. Given that today’s DNA databases consist primarily of DNA from people of European ancestry, some say DNA phenotyping is based on incomplete data.

In 2016 the American Civil Liberties Union argued that law enforcement should refrain from circulating sketches of suspects based on DNA phenotyping until there is more peered-reviewed scientific evidence of their accuracy. Doing otherwise risks subjecting people to suspicion based on their similarity to images based on broad descriptions. [6]

Such concerns have prompted lawmakers to take a cautious approach. As recently as 2018, several legislatures prohibited use of official state data for DNA phenotyping, while others prohibit the use of DNA analysis for the sole purpose of identifying physical characteristics.

Building the case for Crush

Parabon has responded to skeptics by opening Parabon Crush™ to peer review. In a 2016 study funded in part by the National Geographic Society, researchers at The University of North Texas Health Science Center found that the company’s Snapshot DNA Phenotyping service predicted skin color, eye color hair color, freckling and ancestry of 24 ethnically diverse subjects consistent with their actual physical appearance. [7] Among the authors was Bruce Budowle, who pioneered the development and use of forensic science during a 26-year career with the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

In 2017, it released the stochastic search algorithm it uses to predict phenotypes – dubbed “Crush” – to peer review by submitting a paper on the topic to the journal BioData Mining. [8] Developed with funding from the National Institutes of Health, Crush models the random and complex interaction of genes based on the same genome-wide association studies used by medical researchers to find SNPs.

In 2018, Parabon retooled its Snapshot service business model n 2018 to add genetic genealogy and kinship inference research after Colorado investigators announced they had identified the Aurora Hills serial killer not from a sketch based on its DNA phenotyping, but by finding his DNA in a public genealogical database.

Today the company offers law enforcement agencies two tiers of DNA phenotyping. It charges $1,500 for a basic DNA phenotype report which includes a textual description and confidence statements of predicted eye color, hair color, skin color, freckling, and sub-continent) ancestry proportions. Advanced phenotyping, which includes face morphology, heat maps and full Snapshot composite, is an additional $1,680. That’s well below the $4,000 to $5,000 Parabon charged for those services five years ago.

A review of success stories on Parabon’s website indicates police have solved significantly more cold cases using the company’s DNA genetic genealogy service, which has sparked a boisterous debate in New York and other states over whether DNA analysis by commercial labs should be permitted in criminal investigations.

Imagining the future

As DNA databases become more inclusive and bioinformatics more sophisticated, researchers will no doubt continue eliminating some of DNA phenotyping’s limitations and build support for its broad adoption by law enforcement.

As DNA databases become more inclusive and bioinformatics more sophisticated, researchers will no doubt continue eliminating some of DNA phenotyping’s limitations and build support for its broad adoption by law enforcement.

In Europe, a consortium of leading universities and national law enforcement agencies partnered in 2017 to advance the science of constructing composite sketches from DNA traces recovered at crime scenes. The consortium is called VISTAGE, which is an acronym for “visible attributes approached through genomic means.” [9]

While many in law enforcement consider DNA phenotyping a technique of last resort, Seman wrote in 2018 that he sees it becoming routine at local crime labs if prices continue to fall.

“Phenotyping has the potential to impact law enforcement similar to the introduction of fingerprint analysis in the beginning of the twentieth century.”

Many in law enforcement foresee being able to feed a sketch based on DNA phenotyping into facial recognition software for comparison with mug shots stored in databases kept by law enforcement agencies, jail systems, drivers’ license bureaus, passport issuers and even public surveillance video systems in an attempt to identify bodies and suspects.

If and when that happens, you can be sure the debate will be vigorous.

References:

[1] https://www.nbcmiami.com/news/local/South-Florida-Police-Bring-New-Life-to-Cold-Cases-With-DNA-Analysis-483093561.html

[2] https://parabon-nanolabs.com/methods.html

[3] https://www.dovepress.com/dna-phenotyping-current-application-in-forensic-science-peer-reviewed-fulltext-article-RRFMS

[4] Same as above.

[5] https://cpoa.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/CPOA-2017-Journal-vol51-3_01-Full-Journal.pdf

[6] https://www.aclu.org/blog/privacy-technology/medical-and-genetic-privacy/forensic-dna-phenotyping

[7] https://docs.parabon.com/pub/Parabon_Snapshot_Scientific_Poster-ISHI_2016.pdf

[8] https://biodatamining.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13040-017-0139-3#Abs1

[9] http://www.visage-h2020.eu/#summary

Charlie Lunan is a science writer with a background in financial journalism who follows the intersection of genetics, evolution, infectious disease, pollution and business. In addition to his freelance work, he produces a website promoting outdoor recreation and sustainable living within a four-hour drive of his home in Charlotte, N.C.