We use so many words to describe our backgrounds. We talk about heritage, ancestry, race, and ethnicity. Most of us use these words interchangeably, but they don’t mean the same thing.

Cultural identify and genetic ancestry do not always line up. There is no genetics of culture.

This would, perhaps, be an unimportant distinction if it weren’t for the political, social and even economic disadvantages and perks associated with belonging to different groups. The ability to claim a particular background and benefit from both socially-constructed and government-sponsored bonuses (especially when the bonuses are a form of reparations) have added fuel to the cultural appropriation debate. Imitation is no longer the highest form of flattery. The term appropriation alone implies improper use for some unearned gain, not homage.

Distinguishing people who are celebrating distant ancestry from those who are misappropriating a culture is a sticky business. Elizabeth Warren’s claim to Native American ancestry in an Association of American Law School directory caused a political storm, for example. Though she never used the claim as an applicant, critics wonder if her minority listing gave her an unfair, dishonestly attained leg up in staffing decisions.

In this context, the words we use matter. Ethnicity is largely cultural. Race, though determined by our genes, cannot be neatly pigeonholed into the social constructs we often talk about. Ancestry is specifically genetic. Background can refer to either genes or culture.

What we mean when we talk about genetics

With the advent of the genetic age, where average citizens can pay comparatively little to purchase an analysis of their genes by private companies, what exactly are we paying for and what can we learn from the results?

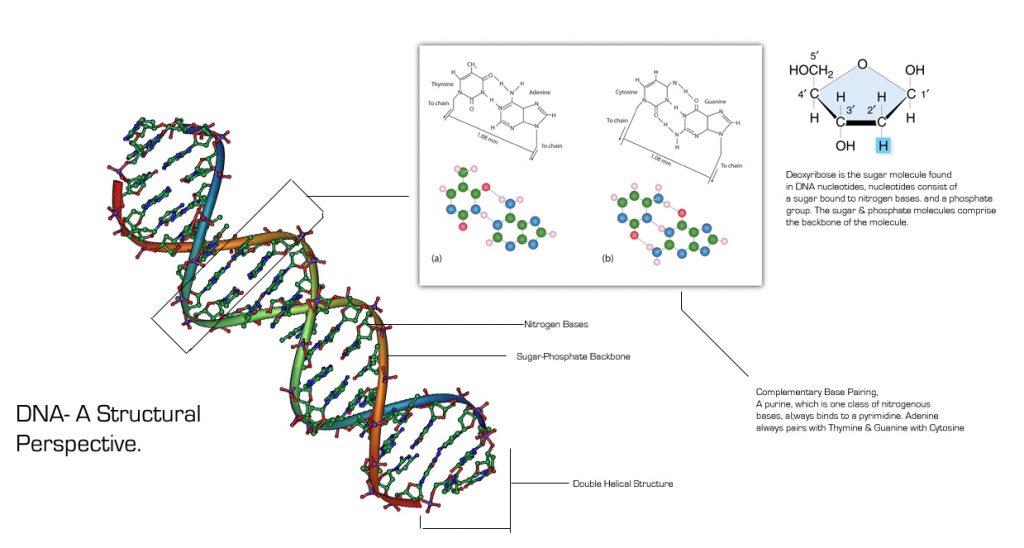

When you send a swab of genetic material for analysis, small snippets of your genes called single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are being compared to genes in a database. Each company has its own proprietary DNA records in its database, taken from modern people hailing from different parts of the world. They each also choose their own set of SNPs to consider when analyzing your genes and use different mathematical algorithms.

Even though the vast majority of human DNA is the same, the relative amount of DNA that these companies use is paltry compared to the possible pieces of genetic information they could use when scanning for differences and similarities. They do, however, likely use the SNPs that most consistently differ between populations in different regions. Why? The tests claim to deliver ancestry results. Though this term is infinitely better than choosing more culturally defined language, the term “ancestor” is misleading.

Though these tests are excellent at finding living relatives, they can’t pinpoint your ancestors.

When a genetic analysis tells you that your “ancestors” came from a certain place, they are really saying that your genes correspond with the genetic variation of people currently living in that place. This is meaningful, but it doesn’t mean exactly what most people think. You can infer that you came from this place, but you can’t know with certainty. Results can be especially misleading if a company has a small dataset from the region of interest or gaps in their dataset where your DNA might be a better match. In much the same way, the percentages given as results are not facts. They are possibilities.

In addition to the limitations already mentioned, there is some evidence to suggest that patterns of epigenetic methylation, modifications to your genes that determine which produce proteins and which do not, are also important to a discussion of heritage. Genetics analysis don’t even touch on these variations.

What we mean when we talk about culture

Unlike genetics, culture is not a science. It is a social construct, making it fluid in nature and subject to distinct interpretations. Culture can be your mother’s hot chocolate recipe, a tradition shared between friends, or family folklore of coming to America. It can be the language you speak at home, religious celebrations, or based on a homeland.

Culture is not nearly as well defined as genetics, leaving many to define and claim their culture as they see fit. It’s more complicated when involving cultures with a long, rich, shared history.

Does a biological test proving ancestry within a region known for a particular culture give a person the right to claim that culture as their own? Does the percentage of their ancestry matter? Is growing up among the traditions of said culture necessary for the claim? Do you have to look like others who share that culture? Can you marry into a culture?

There are no scientific answers these questions, and there never will be.

Chelsea Weidman is a biochemist and freelance science writer/editor interested in genetics, gene editing technologies, stem cells, and novel medications. She has written for Massive and Harvard University’s Science in the News.

Her research has focused on a range of topics such as molecular imaging agents, reversible covalent chemistries, and novel antibiotic strategies. She received her Bachelor of Science degree in Biochemistry and her Master of Science degree in Chemical Biology.